How To Do Automatic Writing

Automatic writing was once a thing: a big thing. Everyone was doing it. At the end of the 19th Century and up to the First World War, everybody was talking to the spirits. This was through raps, voices, apports, or many other apparent manifestations, but what I want to focus on in this article is the art and science of automatic writing.

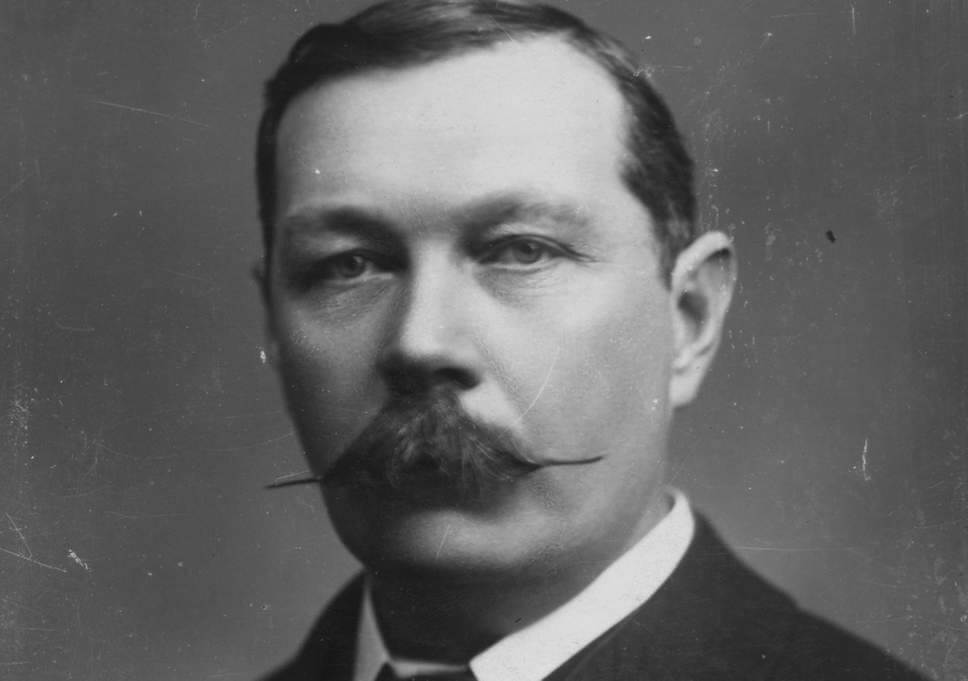

At that time, rather famous people dabbled in this method of extracting information from the spirit world. W B Yeats, the winner of the 1923 Nobel Prize for literature and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a friend of Harry Houdini and creator of Sherlock Holmes, were both great believers in automatic writing.

I don’t want to get hung up on what these “spirits” are. For this article, we will suspend disbelief and accept that the recipients of the automatic writing believed them to be some kind of discarnate, intelligent and independent intelligence.

You can learn automatic writing in fact. Check out this book.

The main question is whether Automatic Writing can produce valuable, actionable information that is reliable, then automatic writing would become a useful tool for all sorts of research. Some practitioners (see Bligh-Bond below) claim to have used it for that very purpose. The critical point is: can the spirits tell us anything useful?

Wikimedia Commons

How To Do Automatic or Spirit Writing

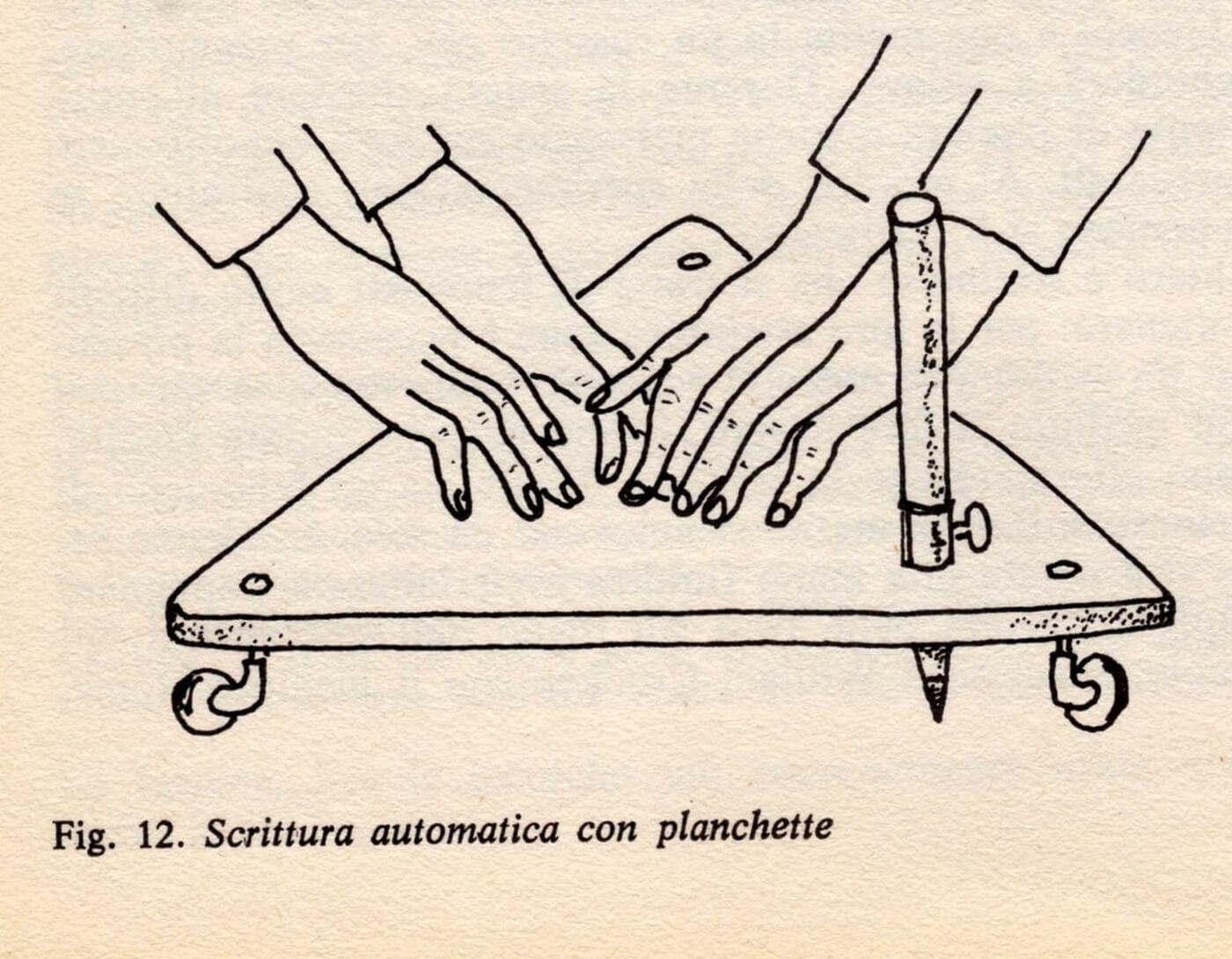

A famous practitioner of automatic writing, or spirit writing, or inspired writing was William Stainton Moses. He wrote a book called Spirit Teachings, published in 1883, where he sets out the method. He describes his technique of obtaining messages from the spirits. Sometimes, he would hold a pen and let the spirit use his hand without any conscious direction from himself, or occasionally he would use a planchette. A planchette (from the French meaning little plank) is a piece of wood, sometimes on rollers, with a hole for a stylus or pencil. You can buy one from Amazon here.

Very interestingly, Stainton Moses says that messages came more easily when writing on tables that were habitually used for that purpose.

At first, he says, the writing was small and irregular, and he had to write cautiously and watch his hand, following the lines with his eye, or the script soon became mere scribble. Does this imply some conscious control?

As Stainton Moses got better at automatic writing, the handwriting became very regular and beautifully formed, he says. He wrote the questions at the top of the page, and then the answers would flow down from them. The spirits had a reasonable command of punctuation, and they would set out their answers in appropriate paragraphs. The words of the spirits were “of sincerity, and of sober, serious purpose,” as befits ghosts writing for a true Victorian.

Over time, Stainton Moses communicated with different sprits. They would sign themselves with their important titles, “Doctor”, “Teacher” and “Rector” and finally the boss spirit “Imperator” (Emperor). Stainton Morris says that the spirits conveyed information that he did not previously know.

Stainton Moses’ spirits give him inspiring words with a Christian, albeit unorthodox Spiritualist Christian flavour. Reading through his book Spirit Teachings, I did not find much valuable teaching that I wanted to absorb and digest, unlike when I’m on Youtube.

Arthur Conan Doyle from Press Weekly

Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle

Conan-Doyle’s series of spirit messages began with communications from his dead father which he describes thus:

“A week after my father’s funeral I was writing a business letter when something seemed to intervene between my hand and the motor centres of my brain, and the hand wrote at an amazing rate a letter, signed with my father’s signature and purporting to come from him. I was upset, and my right side and arm became cold and numb. For a year after this letters came frequently, and always at unexpected times. I never knew what they contained until I examined them with a magnifying glass: they were microscopic. And they contained a vast amount of matter with which it was impossible for me to be acquainted.”

But mainly the automatic writing was transmitted via his wife, Lady Jean Conan Doyle (nee Leckie). The writing began in 1921 and initially consisted of messages from personal friends who had died. In April 1922, Conan Doyle was contacted by his guide Pheneas, and Pheneas was not a deceased friend but a man who lived in Arabia many centuries previously. By 1924, Jean stopped writing and spoke in a trance-like state.

This development moved her onto what is technically channelling. Interestingly, as Automatic Writing died out, channelling became the most prominent method by which the spirits (and aliens, if they aren’t the same thing) spoke to us mere mortals. There are many cases of channelling from, the 1970s and later which we don’t talk about here.

Conan Doyle produced a book called Pheneas Speaks. Conan Doyle calls Automatic Writing “Inspired Writing” to take account that the spirits inspire it. He notes in the preface to the book that information was given, quite often prophecies of the future, but that some of this information was inaccurate.

Conan Doyle was quite convinced that his wife wrote information produced was not within her previous knowledge or awareness. One example of this was when a spirit mentioned an Italian who played cricket who had just died. Conan Doyle says the name was difficult to read but ended in the letters

“-cini.”

Conan Doyle was doubtful about this snippet from the spirit world, as he didn’t know any Italians who could play cricket. Still, a few days later they learned that an Italian called Paravicini who had played cricket for Middlesex died two days before the communication. None present were aware they knew this.

This might be some slight evidence that the information did not originate in Jean’s subconscious. However, other explanations exist, for instance, that she had heard someone mention the cricketer’s passing, in passing, but didn’t remember because the fact had not registered in conscious memory.

Conan Doyle was clear that the spirits were not omniscient and he says they can be wrong as much as we can be wrong.

Reading through Pheneas Speaks, I see that most of the spirits that come to Conan Doyle during these sessions write in Christian terms in line with Conan Doyle’s Christian Spiritualist beliefs. For example, they say the day will soon come when every knee in the world shall bend to Christ. That hasn’t happened yet.

There was nothing much in Conan Doyle’s book of spirit writings that struck me as valuable information. Phineas didn’t inspire any highlighting from me.

William Butler Yeats, Walter De La Mare and Lady Ottoline Morrell, Wikimedia Commons

William Butler Yeats

Yeats, the famous Irish poet, was also a renowned member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and interested in mythology, gods, spirits and ghosts all of his life.

He married a much younger woman Georgina Hyde-Lees, whom he called “George”. She was 25, and he 52 and both were members of the Golden Dawn, and she had a reputation for being psychic. Only days after their wedding, in October 1917 at Ashdown Forest Hotel, Georgina, or “George” as he insisted on calling her because it gave him more opportunity for rhymes, started producing automatic writing.

In the end, there were four thousand pages of this writing. Whereas Conan Doyle’s material was very Christian in Spiritualist in tone, Yeats’s spirits delivered messages in line with the occult and magical world view Yeats was interested in.

This disparity suggests arguments both for and against the truth of spirit communications. The argument against is that they are inconsistent world-views: Yeat’s is occult, Conan Doyle is spiritualist-Christian.

However, the lack of consistency doesn’t prove anything. If you were to visit my house, you would see I have a lot of books of ghost stories, whereas if you went to my mother’s house, you would see she has mainly detective novels. Some folk read ghost stories, and some folk read detective novels. So there may be Christian spirits and Hermetic spirits. Because there are both doesn’t mean there are neither.

In contrast to Conan Doyle’s material, the spirit writing from Yeats’s A Vision, talks about occult systems and refers to Buddhist ideas and Japanese No drama. Yeats’s guide or ‘control’ is called Ameritus. It seems that contacts have to have high falutin’ names. Carl Jung’s contact was Philemon.

Ameritus’s advice to Yeats, amusingly, was to spend more time writing poetry and less reading automatic script.

On reading, the systems expounded by the spirits in what came to be Yeats’s A Vision are linked to the occult systems he sketched out long before the automatic writing began. He’d been interested in this stuff all his life. The spirit writing merely confirmed what he believed anyway. I must admit, I haven’t been able to peruse all of Yeats’s material, but once again, I do not find information that is generally useful to anyone but Yeats. I get more value from click-bait.

Glastonbury Abbey on Pixabay

Frederick Bligh-Bond

The book that contains Frederick Bligh-Bond’s information received by automatic writing is called The Gate of Remembrance. Bligh-Bond had been official archaeologist at the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey from 1908 until 1921 when the Bishop fired him.

Bligh-Bond trained as an architect but had an abiding interest in the occult and the paranormal. Long before he was appointed as archaeologist, he had believed that the Abbey was built according to occult principles, namely the Hebrew Gematria. Gematria links words for mystical rather than philological or semantic reasons. Bligh-Bond believed that Glastonbury Abbey and other cathedrals were built following patterns of occult numbers.

When reading the spirit communications to Bligh-Bond, again the Christian influences are evident. He was brought up an Anglican (Episcopalian), and his father was an Anglican vicar. His education and erudition are also apparent; for example, his ghostly collaborators wrote in Latin and pretty good Middle English. Bligh-Bond approaches the investigations in a thoroughly respectable academic manner, and the book resembles a paper for one of the antiquarian journals of the day until he mentions he is getting his information from ghosts, via a seer.

Again, as with Conan-Doyle, and Yeats, Bligh-Bond doesn’t do the spirit writing himself, it comes through his colleague Captain Alleyn.

In the writings about Glastonbury Abbey, a whole crowd of monks seek to come through from different historical periods. In one case there’s a Saxon who can’t speak because he’s been dead too long and has the language. Interestingly, the monks write in Latin and in an old-fashioned type of English but never write in Anglo-Saxon.

Bligh-Bond is not happy with the standard of their Latin and says it is the type of Latin you might expect from half-literate monks, using what scraps of Latin they have picked up from their service books. I am not expert enough to analyse the English the monks speak, but it doesn’t look like proper Middle English such as you would find in Chaucer. It looks like ye olde fashioned English spiced with some archaic words, e.g. enow for enough, sen for since and guerdon for a reward.

Similar doubts can be cast on whether the brand of English spoken by the medieval monks is authentically what would have been spoken in those times at Glastonbury. The monks say on several occasions that they are not dead, that what is speaking is only some part of them that is still bound to the Abbey through affection.

Bligh-Bond is most rigorous in his method. He is clear that the information gleaned from the monks enabled him to find previously unknown archaeological structures. His claim, therefore, is that by using ‘psychological’ methods, he was able to obtain objectively verifiable evidence.

But on the face of it, in Bligh-Bond’s case, the automatic writing actually seems to have produced some actionable and accurate information.

Photo by Bee Felten-Leidel on Unsplash

My Own Experience

This personal experience happened some years ago and is the reason for my interest in the topic of automatic writing. At that time in my life, I was a tour guide for ghost tours around haunted castles and other such places in England and Ireland.

There was a place, not too far from me, very historic and very haunted, called Dalston Hall. I must have had forty or more trips to Dalston Hall. Our tour routine was that we would do the tour, then have something to eat in the dining room and then retire to the library.

We lit the library with candles, and I told stories of my own experiences at Dalston Hall, and elsewhere. The bulk of my material was the stories of all the hundreds of people who had come on our ghost trips across Britain and Ireland and told me their own true stories, oOr stories they believed were true.

On our tours, we used electrical field detectors to pick up unusual electrical fields, that existed away from any power source, hanging in the air.

I used the EMF detectors a lot, and I can tell you my hands and arms do not usually have a detectable electrical field. This particular night I had the weirdest sensation in my right hand. It tingled, it felt animated. I scanned my hand with the EMF detector, and the scanner lit up. This isn’t usual and indicates an electrical field. I had the intuition that my hand wanted to write. I had never done anything like that before, but I picked up a pencil and out came this elaborate copperplate writing saying that John Dalston was there. We asked his name and his dates of birth and marriage. I forget exactly when, but it was the early 1600s. We didn’t get much sense out of him, but he said he had married an Irish Catholic woman which would have been extraordinary for an English nobleman in those times. After the writing had finished, I went into the bar, and the bar staff said

“Have you seen a ghost? You’re white….”

After that, I regularly tried to contact John Dalston at Dalston Hall. He came through, but he didn’t have much to say for himself. I was also visited by George Dalston, who had different handwriting. Again, he was also pretty thin as a personality, but on the next visit to Dalston Hall, I tried again and, unexpectedly, a different script appeared on the paper, but still different to mine.

It wrote: “Love”. I thought that was nice and it persisted and wrote: “You are a well-loved fellow”.

It struck me as quite an archaic phrasing, so I asked it who it was and it said. “Rebecca Goffrey”.

I asked Rebecca who she was, and she said, “Your wife.” Now, it so happens that I was married at that time so I made some wisecrack which she ignored.

I asked what my name was and she said, “Davey Goffrey”. She said I was “a watcher for the King”. I still have no idea what that means.

Rebecca said we had a child and that my father was a ropemaker called John. Our son was named John too. I asked her when and where we were married, and she said

“Tuesday, July 14th, 1714 at St Katherine’s Church, London.”

When I managed to look it all up, I saw that July 17th 1714 wasn’t a Tuesday. However, she wrote Katherine with a K, not the more usual C. I didn’t remark on the spelling at the time, though now it seems more significant.

The name Goffrey exists (I hadn’t previously heard of it) and there are several in the London phonebook, but then probably every name under the sun is in the London phonebook. I also looked up churches in London, and there is no St Katherine’s, so I thought the whole thing was a product of my imagination then some years later I was in London, and I saw a sign for St Katherine’s Dock. But now it’s a dock (actually a swanky marina), not a church.

However, in the Middle Ages, where St Katherine’s Dock now is, was a hospital founded by a religious order, and this hospital was dedicated to St Katherine and built around a church. The church was knocked down in 1825 to make way for the dock development. I did not know this when the automatic writing came through, but it was a densely populated area, and people got married there.

I am guessing that the name Goffrey is a variant of the more common Geoffrey. The whole episode was odd. Rebecca doesn’t write to me anymore, but it’s still nice to think that someone out there in the ether thinks I am a well-loved fellow.

Is Automatic Writing Merely Confabulation?

What to make of all this spirit writing? Perhaps there’s a clue in the feature known as confabulation.

Confabulation is a clinical feature of Korsakoff’s Syndrome, a condition induced by chronic depletion of B vitamins caused by alcoholism. In this condition, people will speak fluently, grammatically and at length reporting experiences which have not happened but they are conviced they have. These utterances are characterised by a poverty of content. They can be quite fantastical and go on at length, but don’t convey any real information.

Confabulation can also occur in amnesia caused by brain disease or injury. Where there are considerable gaps in memory, the sufferer will simply make long, often involved, stories up. Again, they mostly don’t contain any valuable content and are long speeches saying nothing much.

It should be noted that confabulation is an unconscious process. The person producing the spouts of words believes what they are saying is real and genuine.

Conclusion

There’s always a conclusion! The Automatic Writing of the various spirits is often flowery and high-sounding, but the actual informational content is minimal.

However, why don’t you try automatic writing for yourself? You might get more value out of it than I did.