The Flannan Isles Disappearance

Mystery of the Flannan Isles Disappearance

The Flannan Isles Disappearance is one of the most enduring maritime mysteries of the early 20th century. In 1900, three lighthouse keepers vanished from the Eilean Mòr lighthouse without a trace, leaving behind only cryptic messages and unanswered questions. The mystery of their disappearance has captivated people around the world and has become a part of Scottish folklore and legend.

Despite extensive investigation and research over the years, the truth behind the Flannan Isles mystery remains a haunting and unsolved enigma.

WHERE ARE THE FLANNAN ISLES?

The Flannan Isles, also known as the Seven Hunters or in Scottish Gaelic: Na h-Eileanan Flannach, are a tiny group of islands in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides, about 32 kilometres (17+12 nautical miles) west of the Isle of Lewis. They might get their name from Saint Flannan, an Irish priest and abbot who lived in the seventh century.

Since the Flannan Islands Lighthouse was automated in 1971, there haven’t been any year-round occupants living on the islands.

The Flannan Isles are divided into three groups: the main cluster to the northeast contains the two largest islands, Eilean Mòr and Eilean Taighe, with Soray and Sgeir Tomain to the south, and Eilean a’ Ghobha, Roaireim, and Bròna Cleit to the west. The total land area is approximately 50 hectares, with the highest point at 88 metres above sea level on Eilean Mòr.

The geology consists of a dark breccia of gabbros and dolerites, and the islands were likely part of a larger land mass before rising sea levels reduced them to their current size. There are two potential landing places for yachts, but the heavy swells make this a hazardous undertaking.

HISTORY OF THE FLANNAN ISLES

Eilean Taighe features a ruined stone shelter, while Eilean Mòr is home to the lighthouse and a ruined chapel dedicated to Saint Flannán, which the lighthouse keepers nicknamed the “dog kennel” due to its small size.

The Ancient Monuments Commission referred to both ruined buildings as The Bothies of the Clan McPhail, or Bothain Chlann ‘ic Phaill.

The identity of the St. Flannan honored by the chapel is unclear, but it is believed to be either the 7th-century Abbot of Killaloe in Ireland or the half-brother of the 8th-century St. Ronan, after whom the nearby island of North Rona is named.

Another possibility is Flann, the son of an Abbot of Iona, who died in 890 and may have also lent his name to the islands. The archipelago is also known as The Seven Hunters or Seven Holy Isles, and during the Middle Ages, the islands were associated with unusual customs such as removing one’s hat and making a sunwise turn when reaching the plateau, according to Martin Martin’s writings in 1703.

The Flannan Isles Mystery

The Flannan Isle Lighthouse Mystery, also called the Flannan Isles Mystery, is about the disappearance of three lighthouse keepers from the Flannan Isles Lighthouse in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. Their disappearance is still a mystery. In December 1900, there was no sign of Thomas Marshall, James Ducat, or Donald McArthur.

The lighthouse had three keepers who worked in shifts to keep the light going and make sure it worked. On December 15, 1900, relief keeper Joseph Moore went to the island to take over for one of the three keepers. However, none of the three men could be found. Moore looked into it and found that the beds weren’t made, the clock wasn’t working, and none of the lamps were on. The only clue to what had happened was a set of oilskins that had been left out. This meant that one of the men had probably gone outside without proper weather protection.

An investigation was started, and people were sent to the island to look for the men, but they were never found. The only strange thing they found was that the entrance gate to the compound was locked from the inside. This was strange because the keepers should have been inside. Theories about what happened to the three men include that they were swept out to sea by a sudden storm, that they were attacked by pirates or foreign spies, or that ghosts or other paranormal things did it.

The mystery of what happened to the Flannan Isle lighthouse keepers hasn’t been solved to this day.

Newspaper report from 1900 on the mysterious disappearance of the crew at the Flannan Isles Lighthouse

On 26 December 1900, the relief crew for the Flannan Isles Lighthouse (located in the Outer Hebrides, 20 miles west of Lewis), arrived at the lighthouse station only to find that the three keepers had vanished.

The beds were unmade, the clock had stopped and an overturned chair in the kitchen were some of the details that were logged by the relief crew in an effort to work out what had happened.

But as with the unfinished story of the ‘Marie Celeste’, it seems that the unexplained fate of the three keepers (Thomas Marshall, James Ducat and Donald Macarthur) will remain yet another of the sea’s enduring mysteries…

Northants Evening Telegraph – Thursday 27 December 1900

On December 15, 1900, something awful happened to the lighthouse keepers on Flannan Isles in the Outer Hebrides, although no one is certain what exactly happened to them today.

The Eilean Mòr lighthouse on the Flannan Isles had been in use for a year by 1900. John Ducat, Thomas Marshall, and Donald McArthur were the three keepers in charge of it.

The light had been out for ten days when the relief vessel Hesperus arrived on December 26 with new supplies.

The island was uninhabited when the ship’s crew arrived; although the kitchen and machinery had been cleaned, there was no evidence of the three keepers.

TELEGRAM FROM MASTER OF HESPERUS SENT ON 26 DECEMBER 1900

A dreadful accident has happened at Flannans. The three Keepers, Ducat, Marshall and the occasional have disappeared from the island. On our arrival there this afternoon no sign of life was to be seen on the Island. Fired a rocket but, as no response was made, managed to land Moore, who went up to the Station but found no Keepers there. The clocks were stopped and other signs indicated that the accident must have happened about a week ago. Poor fellows they must been blown over the cliffs or drowned trying to secure a crane or something like that. Night coming on, we could not wait to make something as to their fate. I have left Moore, MacDonald, Buoymaster and two Seamen on the island to keep the light burning until you make other arrangements. Will not return to Oban until I hear from you. I have repeated this wire to Muirhead in case you are not at home. I will remain at the telegraph office tonight until it closes, if you wish to wire me.

Master, HESPERUS

“Captain Harvie was in command of the Hesperus. We reported that on arrival at the Flannans during the afternoon of 26 December there was no sign of life to be seen on the Island and no response was made to a rocket fired from the ship…

“…The last written entries in the log were for 13 December, but particulars for 14 December and of the time extinguishing the light on 15 December, along with barometer and thermometer readings and state of the wind taken at 9 am on 15 December, were noted on the slate for transference later to the log.

…Everything was in order, the lamp ready to be lit, and it was evident that the work of the forenoon of the 15th had been completed, indicating that the men disappeared on the afternoon of Saturday 15 December”.

(From records of the Northern Lighthouse Board, 1901).

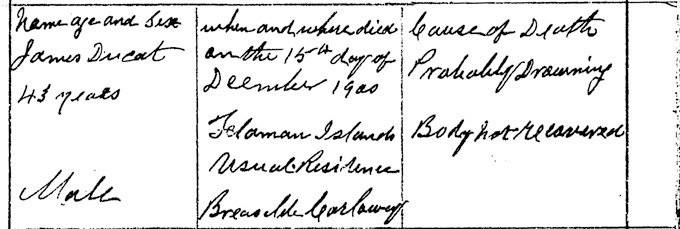

In 1901, the cause of their deaths was recorded as “Perhaps drowning, bodies not retrieved.”

Letter From Joseph Moore, Assistant Lightkeeper

Sir

It was with deep regret I wish you to learn the very sad affair that has taken place here during the past fortnight; namely the disappearance of my two fellow lightkeepers Mr Ducat and Mr Marshall, together with the Occasional Keeper, Donald McArthur from off this Island.

As you are aware, the relief was made on the 26th. That day, as on other relief days, we came to anchorage under Flannan Islands, and not seeing the Lighthouse Flag flying, we thought they did not perceive us coming. The steamer’s horn was sounded several times, still no reply. At last Captain Harvie deemed it prudent to lower a boat and land a man if it was possible. I was the first to land leaving Mr McCormack and his men in the boat till I should return from the lighthouse. I went up, and on coming to the entrance gate I found it closed. I made for entrance door leading to the kitchen and store room, found it also closed and the door inside that, but the kitchen door itself was open. On entering the kitchen I looked at the fireplace and saw that the fire was not lighted for some days. I then entered the rooms in succession, found the beds empty just as they left them in the early morning.

I did not take time to search further, for I only too well knew something serious had occurred. I darted out and made for the landing. When I reached there I informed Mr McCormack that the place was deserted. He with some of the men came up second time, so as to make sure, but unfortunately the first impression was only too true. Mr McCormack and myself proceeded to the lightroom where everything was in proper order. The lamp was cleaned. The fountain full. Blinds on the windows etc. We left and proceeded on board the steamer. On arrival Captain Harvie ordered me back again to the island accompanied with Mr McDonald (Buoymaster), A Campbell and A Lamont who were to do duty with me till timely aid should arrive. We went ashore and proceeded up to the lightroom and lighted the light in the proper time that night and every night since. The following day we traversed the Island from end to end but still nothing to be seen to convince us how it happened. Nothing appears touched at East landing to show that they were taken from there. Ropes are all in their respective places in the shelter, just as they were left after the relief on the 7th.

On West side it is somewhat different. We had an old box halfway up the railway for holding West landing mooring ropes and tackle, and it has gone. Some of the ropes it appears, got washed out of it, they lie strewn on the rocks near the crane. The crane itself is safe.

The iron railings along the passage connecting railway with footpath to landing and started from their foundation and broken in several places, also railing round crane, and handrail for making mooring rope fast for boat, is entirely carried away. Now there is nothing to give us an indication that it was there the poor men lost their lives, only that Mr Marshall has his seaboots on and oilskins, also Mr Ducat has his seaboots on. He had no oilskin, only an old waterproof coat, and that is away. Donald McArthur has his wearing coat left behind him which shows, as far as I know, that he went out in shirt sleeves. He never used any other coat on previous occasions, only the one I am referring to.

Mr J. Moore,

Assistant Lightkeeper,

Flannan Islands Lighthouse

28 December 1900

Report submitted by Robert Muirhead, Superintendent, on the 8 January 1901

On receipt of Captain Harvie’s telegram on 26 December 1900 reporting that the three keepers on Flannan Islands, viz James Ducat, Principal, Thomas Marshall, second Assistant, and Donald McArthur, Occasional Keeper (doing duty for William Ross, first Assistant, on sick leave), had disappeared and that they must have been blown over the cliffs or drowned, I made the following arrangements with the Secretary for the temporary working of the Station.

James Ferrier, Principal Keeper was sent from Stornoway Lighthouse to Tiumpan Head Lighthouse and John Milne, Principal Keeper at Tiumpan Head was sent to take temporary charge at Flannan Islands. Donald Jack, the second Assistant Storekeeper was also despatched to Flannan Islands, the intention being that these two men, along with Joseph Moore, the third Assistant at Flannan Islands, who was ashore when the accident took place, should do duty pending permanent arrangements being made. I also proceeded to Flannan Islands where I was landed, along with Milne and Jack, early on the 29th.

After satisfying myself that everything connected with the light was in good order and that the men landed would be able to maintain the light, I proceeded to ascertain, if possible, the cause of the disaster and also took statements from Captain Harvie and Mr McCormack the second mate of the HESPERUS, Joseph Moore, third Assistant keeper, Flannan Islands and Allan MacDonald, Buoymaster and the following is the result of my investigations:-

The HESPERUS arrived at Flannan Islands for the purpose of making the ordinary relief about noon Wednesday, 26 December and, as neither signals were shown, nor any of the usual preparations for landing made, Captain Harvie blew both the steam whistle and the siren to call the attention of the Keepers. As this had no effect, he fired a rocket, which also evoked no response, and a boat was lowered and sent ashore to the East landing with Joseph Moore, Assistant Keeper. When the boat reached the landing there being still no signs of the keepers, the boat was backed into the landing and with some difficulty Moore managed to jump ashore. When he went up to the Station he found the entrance gate and outside doors closed, the clock stopped, no fire lit, and, looking into the bedrooms, he found the beds empty. He became alarmed at this and ran down to the boat and informed Mr McCormack and one of the seamen managed to jump ashore and with Moore made a thorough search of the Station but could discover nothing. They then returned to the ship and informed Captain Harvie who told Moore he would have to return to the Island to keep the light going pending instructions, and called for volunteers from his crew to assist in this.

He met with a ready response and two seamen, Lamont and Campbell, were selected with Mr MacDonald, the Buoymaster, who was on board, also offered his services, which were accepted and Moore, MacDonald and these two seamen were left in charge of the light while Captain Harvie returned to Breasclete and telegraphed an account of the disaster to the Secretary.

The men left on the Island made a thorough search, in the first place, of the Station and found that the last entry on the slate had been made by Mr Ducat, the Principal Keeper on the morning of Saturday, 15 December. The lamp was crimmed, the oil fountains and canteens were filled up and the lens and machinery cleaned, which proved that the work of the 15th had been completed. The pots and pans had been cleaned and the kitchen tidied up, which showed that the man who had been acting as cook had completed his work, which goes to prove that the men disappeared on the afternoon which was received (after news of the disaster had been published) that Captain Holman had passed the Flannan Islands in the steamer ARCHTOR at midnight on the 15th ulto, and could not observe the light, he felt satisfied that he should have seen it.

On the Thursday and Friday the men made a thorough search over and round the island and I went over the ground with them on Saturday. Everything at the East landing place was in order and the ropes which had been coiled and stored there on the completion of the relief on 7 December were all in their places and the lighthouse buildings and everything at the Stations was in order. Owing to the amount of sea, I could not get down to the landing place, but I got down to the crane platform 70 feet above the sea level. The crane originally erected on this platform was washed away during last winter, and the crane put up this summer was found to be unharmed, the jib lowered and secured to the rock, and the canvas covering the wire rope on the barrel securely lashed round it, and there was no evidence that the men had been doing anything at the crane. The mooring ropes, landing ropes, derrick landing ropes and crane handles, and also a wooden box in which they were kept and which was secured in a crevice in the rocks 70 feet up the tramway from its terminus, and about 40 feet higher than the crane platform, or 110 feet in all above the sea level, had been washed away, and the ropes were strewn in the crevices of the rocks near the crane platform and entangled among the crane legs, but they were all coiled up, no single coil being found unfastened. The iron railings round the crane platform and from the terminus of the tramway to the concrete steps up from the West landing were displaced and twisted. A large block of stone, weighing upwards of 20 cwt, had been dislodged from its position higher up and carried down to and left on the concrete path leading from the terminus of the tramway to the top of the steps.

A life buoy fastened to the railings along this path, to be used in case of emergency had disappeared, and I thought at first that it had been removed for the purpose of being used but, on examining the ropes by which it was fastened, I found that they had not been touched, and as pieces of canvas was adhering to the ropes, it was evident that the force of the sea pouring through the railings had, even at this great height (110 feet above sea level) torn the life buoy off the ropes.

When the accident occurred, Ducat was wearing sea boots and a waterproof, and Marshall sea boots and oilskins, and as Moore assures me that the men only wore those articles when going down to the landings, they must have intended, when they left the Station, either to go down to the landing or the proximity of it.

After a careful examination of the place, the railings, ropes etc and weighing all the evidence which I could secure, I am of opinion that the most likely explanation of the disappearance of the men is that they had all gone down on the afternoon of Saturday, 15 December to the proximity of the West landing, to secure the box with the mooring ropes, etc and that an unexpectedly large roller had come up on the Island, and a large body of water going up higher than where they were and coming down upon them had swept them away with resistless force.

I have considered and discussed the possibility of the men being blown away by the wind, but, as the wind was westerly, I am of the opinion, notwithstanding its great force, that the more probably explanation is that they have been washed away as, had the wind caught them, it would, from its direction, have blown then up the Island and I feel certain that they would have managed to throw themselves down before they had reached the summit or brow of the Island.

On the conclusion of my enquiry on Saturday afternoon, I returned to Breasclete, wired the result of my investigations to the Secretary and called on the widows of James Ducat, the Principal Keeper and Donald McArthur, the Occasional Keeper.

I may state that, as Moore was naturally very much upset by the unfortunate occurrence, and appeared very nervous, I left A Lamont, Seaman, on the Island to go to the lightroom and keep Moore company when on watch for a week or two.

If this nervousness does not leave Moore, he will require to be transferred, but I am reluctant to recommend this, as I would desire to have one man at least who knows the work of the Station.

The Commissioners appointed Roderick MacKenzie, Gamekeeper, Uig, near Meavaig, to look out daily for signals that might be shown from the Rock, and to note each night whether the light was seen or not seen. As it was evident that the light had not been lit from the 15th to the 25th December, I resolved to see him on Sunday morning, to ascertain what he had to say on the subject. He was away from home, but I found his two sons, ages about 16 and 18 – two most intelligent lads of the gamekeeper class, and who actually performed the duty of looking out for signals – and had a conversation with them on the matter, and I also examined the Return Book. From the December Return, I saw that the Tower itself was not seen, even with the assistance of a powerful telescope, between the 7th and the 29th December. The light was, however, seen on 7th December, but was not seen on the 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th. It was seen on the 12th, but not seen again until the 26th, the night on which it was lit by Moore. MacKenzie stated (and I have since verified this), that the lights sometimes cannot be seen for four of five consecutive nights, but he was beginning to be anxious at not seeing it for such a long period, and had, for two nights prior to its reappearance, been getting the assistance of the natives to see if it could be discerned.

Had the lookout been kept by an ordinary Lightkeeper, as at Earraid for Dubh Artach, I believe it would have struck the man ashore at an earlier period that something was amiss, and, while this would note have prevented the lamentable occurrence taking place, it would have enabled steps to have been taken to have the light re-lit at an earlier date. I would recommend that the Signalman should be instructed that, in future, should he fail to observe the light when, in his opinion, looking to the state of the atmosphere, it should be seen, he should be instructed to intimate this to the Secretary, when the propriety of taking steps could be considered.

I may explain that signals are shown from Flannan Islands by displaying balls or discs each side of the Tower, on poles projecting out from the Lighthouse balcony, the signals being differentiated by one or more discs being shown on the different sides of the Tower. When at Flannan Islands so lately as 7th December last, I had a conversation with the late Mr Ducat regarding the signals, and he stated that he wished it would be necessary to hoist one of the signals, just to ascertain how soon it would be seen ashore and how soon it would be acted upon.

At that time, I took a note to consider the propriety of having a daily signal that all was well – signals under the present system being only exhibited when assistance of some kind is required. After carefully considering the matter, and discussing it with the officials competent to offer an opinion on the subject, I arrived at the conclusion that it would not be advisable to have such a signal, as, owing to the distance between the Island and the shore, and to the frequency of haze on the top of the Island, it would often be unseen for such a duration of time as to cause alarm, especially on the part of the Keepers’ wives and families, and I would point out that no day signals could have been seen between the 7th and 29th December, and an “All Well” signal would have been of no use on this occasion.

The question has been raised as to how we would have been situated had wireless telegraphy been instituted, but, had we failed to establish communication for some days, I should have concluded that something had gone wrong with the signalling apparatus, and the last thing that would have occurred to me would have been that all the three men had disappeared.

In conclusion, I would desire to record my deep regret at such a disaster occurring to Keepers in this Service. I knew Ducat and Marshall intimately, and McArthur the Occasional, well. They were selected, on my recommendation, for the lighting of such an important Station as Flannan Islands, and as it is always my endeavour to secure the best men possible of the establishment of a Station, as the success and contentment at a Station depends largely on the Keepers present at its installation, this of itself is an indication that the Board has lost two of it most efficient Keepers and a competent Occasional.

I was with the Keepers for more than a month during the summer of 1899, when everyone worked hard to secure the early lighting of the Station before winter, and, working along with them, I appreciated the manner in which they performed their work. I visited Flannan Islands when the relief was made so lately as 7th December, and have the melancholy recollection that I was the last person to shake hands with them and bid then adieu.

Robert Muirhead, Superintendent, 8 January 1901

The Missing Lighthouse Men

At the time of the Flannan Isles Lighthouse Mystery in 1900, the lighthouse was equipped with a powerful Fresnel lens, which was the cutting-edge technology of its time. The lens was designed to cast a bright, visible beam of light over long distances to guide ships safely through treacherous waters, even in poor visibility or at night.

The lighthouse was also powered by a clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens, and it had a foghorn to warn ships of hazards in low-visibility conditions. The lighthouse was designed to be fully automated, but it still required three lighthouse keepers to maintain the equipment and ensure that it operated correctly.

The family histories of the lighthouse keepers that vanished from the Flannan Islands lighthouse in 1900 are little documented. Yet, the following is known:

James Ducat was born in Edinburgh, Scotland in the year 1848. He was wed to Margaret (Maggie) Cooper, with whom he had two children. Regarding his parents and other family members, little is known.

Thomas Marshall was born in 1849 in the Scottish city of Dundee. Together, he and his wife Mary Jane (Minnie) Kelsall had one daughter. His father was a shipmaster, but little else about his family is known.

Donald MacArthur was born on the Scottish island of Lewis in 1862. He had a wife named Flora MacKenzie, and the couple had six children. Malcolm and Mary MacArthur, who were also from the Isle of Lewis, were Donald’s parents.

Beyond these fundamental data, there is not much information available regarding the family histories of the lighthouse keepers. Yet, it is known that the disappearance had a profound impact on the families of the lighthouse keepers, and that the tragedy had a lasting effect on their lives.

Folklore Of The Flannan Isles

Since the Flannan Isles have been inhabited and utilised for a variety of purposes for many years, they are mentioned in a number of historical documents. The Flannan Isles are mentioned in one of the earliest recorded accounts from the sixth century.

The Vita Columbae (Life of Saint Columba), written by the historian and chronicler Adamnan, claims that the Flannan Isles were visited by the Irish monk St. Columba in 577 AD. The story goes that while sailing by boat, St. Columba and his followers spotted a number of angels on the shore of the largest island, which they took to be a symbol of the island’s purity.

Other historical documents, such as Norse sagas and mediaeval chronicles, also refer to the Flannan Isles. The islands were referenced in the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, a Latin-language account of Scottish history, written in the 12th century.

The Flannan Isles have been used for a variety of activities over the years, including farming, fishing, and kelp production. One of the most well-known monuments on the islands is the lighthouse on Eilean Mor, which was constructed in the late 19th century to aid with nautical navigation.

According to an article in The Scotsman, the Flannan Isles have long been associated with supernatural legends and folklore. The islands are said to be haunted by the ghosts of sailors who were shipwrecked on their shores, and many people have reported seeing ghostly apparitions and other strange phenomena on the islands over the years.

The Flannan Isles are also the setting for a famous Gaelic ballad called “Eilean Mor” (Big Island), which tells the story of a young woman who is lured to the islands by a supernatural force and is never seen again. The ballad has been recorded by many artists over the years and has become a well-known part of Scottish folklore.

Wider Considerations

The Flannan Isle Lighthouse Mystery is significant from a historical perspective as it represents a critical moment in the development of lighthouse technology, which was becoming essential to maritime safety. The disappearance of the lighthouse keepers drew attention to the risks associated with working in remote and challenging environments and prompted safety changes and increased communication with the mainland.

Politically, the incident occurred during a time when the British Empire was at the height of its power, and the United States was emerging as a global power. The lighthouse was a crucial navigational aid for ships traveling through the treacherous waters around the British Isles and was a technological achievement that highlighted the importance of maintaining maritime power.

From a journalistic perspective, the Flannan Isle Lighthouse Mystery demonstrates how the media can create and shape public interest in a particular story. The sensationalist and often speculative media coverage of the disappearance showed how journalism was evolving and becoming more about entertaining and engaging readers rather than just reporting the news.

The story also has cultural and folklore significance, with the Flannan Isles being an important part of Scottish folklore and legend. Additionally, the disappearance of the lighthouse keepers highlights the dangers of working in harsh and unpredictable environments and emphasizes the importance of taking precautions and being prepared for unexpected events.

The Mystery is Embroidered

The romanticised 1912 poem Flannan Island by the poet Wilfrid Gibson added to the mystery’s continuing appeal.

Gibson added several terrifying fictions, such as an unfinished lunch, a chair that has fallen over, and three “strange, black, ugly birds” that are about to disappear.

“And, as into the tiny creek

We stole beneath the hanging crag,

We saw three queer, black, ugly birds –

Too big, by far, in my belief,

For guillemot or shag –

Like seamen sitting bolt upright

Upon a half-tide reef:

But, as we neared, they plunged from sight,

Without a sound, or spurt of white…”

The tale also sent children of the 1970s scurrying behind their sofas, as the inspiration for the classic Doctor Who story The Horror of Fang Rock in 1977. The story ends with Tom Baker (The Doctor) quoting from Gibson’s poem.

Over the years, the Flannan Isles mystery has generated many outlandish theories and ideas, some of which are quite far-fetched. One of the most outlandish theories about the Flannan Isles mystery is that the lighthouse keepers were abducted by a giant sea monster.

This theory suggests that a massive sea creature, such as a giant squid or octopus, may have attacked the lighthouse keepers and dragged them into the sea. This theory is based on reports of large sea monsters in the waters around the Flannan Isles, as well as the absence of any concrete evidence or explanation for the disappearance.

While this theory may seem far-fetched and is not supported by any credible evidence, it highlights the enduring mystery and intrigue surrounding the Flannan Isles disappearance. The lack of concrete answers has led to many creative and imaginative theories over the years, some more outlandish than others.

Other Disappearances

Yes, there were several other unexplained disappearances that occurred around the turn of the 19th century that have become the subject of similar mystery and speculation, similar to the Flannan Isles disappearance. Here are a few examples:

THE MARY CELESTE:

In 1872, the crew of the American merchant ship Mary Celeste disappeared without a trace. The ship was found adrift in the Atlantic Ocean with no one aboard, and the disappearance of the crew remains a mystery to this day.

THE CARROLL A. DEERING:

In 1921, the Carroll A. Deering, a five-masted schooner, was found abandoned off the coast of North Carolina. The entire crew had disappeared, and the mystery of their disappearance has never been solved.

THE USS CYCLOPS:

In 1918, the USS Cyclops, a United States Navy cargo ship, disappeared in the Bermuda Triangle with 306 crew members aboard. The ship’s disappearance remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in maritime history.

THE S.S. WARATAH:

In 1909, the S.S. Waratah, an Australian passenger ship, disappeared without a trace while sailing from Durban, South Africa to London. The ship and its 211 passengers and crew were never found, and the disappearance remains a mystery to this day.

These disappearances share similarities with the Flannan Isles mystery in that they involved the sudden and unexplained disappearance of people or ships. They have all captured the public imagination and have become enduring mysteries that continue to fascinate and intrigue people around the world.

References

http://www.potw.org/archive/potw230.html